From the basement, through the maze and onto the roof—and back again

What is the connection between an exhibition in the National Museum, the closure of a dairy and the formation of techno culture in Zurich? We go looking for clues with Nicholas Schärer, a lecturer on the Cast/ Audio visual Media subject area in the Department of Design.

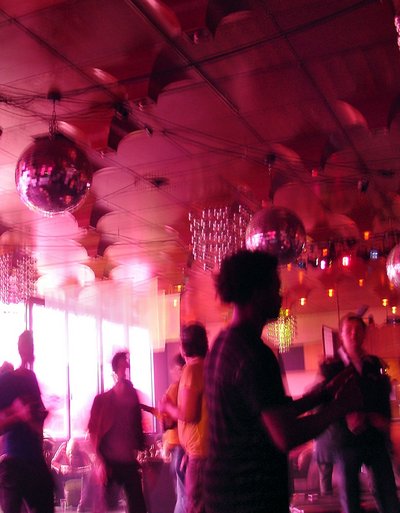

Raw concrete and the sort of dimensions you associate with industrial buildings. These are what characterize the extension to the National Museum in Zurich. For four months, a lonely-looking DJ booth, mounted on scaffolding, enjoyed pride of place above the monumental staircase at the entrance. It captured a bit of the vibe you get in massive techno clubs to be found in many European cities over recent decades. A gesture that is as conclusive as it is ambivalent. After all, does the embrace by this state cultural institution not also show that an innovative subculture has been canonized and is now ready for the museum? The TECHNO exhibition covered a lot of ground, ranging from the history of techno music (including a nostalgic-feeling record shop with listening stations) to issues concerning style, gender and diversity, the various motivations that encouraged people to listen, party and dance, and the places where it all comes—or rather came—together. Because the days are gone when techno was considered avant-garde and set the trend in terms of nightlife.

A time of experimentation

Nicholas Schärer got into electronic music and its communities through mixtapes and raves in the Jura region, Bern, Basel, Lucerne and, of course, Zurich. The ’90s saw a blossoming of techno culture, both in the centre and the periphery. With the factories in the west of Zurich now closed and the workers having left the district, spaces were suddenly becoming available in a city that had enjoyed something of a problematic reputation just a few years before – as a place more conducive to business than pleasure. The empty warehouses, underground car parks and squats provided space to try things that could not be done elsewhere. The result was an emerging ecosystem of legal, semi-legal and illegal events. People with an interest in this emerging culture, like Schärer, soon made connections and found opportunities to get involved.

The art of organization

“In the early ’00s, cultural events in squatted spaces were an integral part of Zurich’s nightlife. And the club scene was far more tied in with the squatting scene than today. The last twenty years have seen a great deal of diversification and professionalization within the club scene. But collaborative structures are intrinsically designed to promote the sharing of knowledge and skills. This meant that I was able to learn my craft and also found space for musical experimentation,” explains Schärer. From 2007, he ran a DIY label with friends, which was mainly focused on local musicians. The label -OUS was founded in 2015, as was the music publisher Shutter Music. “It is important for me to run the music label in a serious manner and make it financially sound. You cannot really make money with music these days—especially if it is not compatible with Spotify or TikTok. Music has the power to grab you there and then; this direct transfer of cultural content into feelings is why it still has a hold on me, even after eighteen years.” The label offers professional structures to selected musicians. Around half of these come from Switzerland, where costs can be covered through funding. The income from record sales and events is then used to support productions by musicians from other countries.

A love of the niche

Music is not an end in itself: it needs spaces where it can resonate, in both the literal and figurative sense of the word. And it is made in a social context. Schärer is interested in the interplay and overlap between the characteristics of a place and a certain type of music and scene. Like when, in his words, “fifteen to sixty people go to a strange concert in a strange place.” It is a love of the niche that wants to achieve something very real: to enable a community, no matter how small, to enjoy the kind of experience it has been searching for. This is what prompted him to co-found Umbo, a “non-commercial space for unconventional music” in an underpass at the former Letten railway station. And why he joined the team behind Rhizom, a transdisciplinary, collectively organized music and arts festival, which has been staged four times so far at the cultural centre Rote Fabrik.

Transfer of knowledge and ideas

Over the years, Schärer has found a space at the “intersection between culture, music and media”, where interests can play out, follow new directions through a process of experimentation and continue to evolve within new areas of activity. This also includes his work as a lecturer in the Major in “Cast / Audiovisual Media” at the Department of Design. The role allows him to implement some projects on a voluntary basis and also facilitates a two-way transfer of ideas and knowledge between the institutional context and the independent scene. “ZHdK is probably one of the few places where it is still possible to think and work in a process-oriented way, without knowing exactly what kind of product should emerge. But even that is coming under an immense amount of pressure.” A current project has seen Schärer come up with a contribution for the National Museum alongside Cast students Ronja Bollinger and Chiara Temmel and alumnus Tillo Spreng. This project traces a thread between the interim use of the discontinued Toni dairy factory as a cultural hub, the TECHNO exhibition celebrating this period and ZHdK’s presence on the Toni Campus today. Outside clubs in Zurich and Geneva and at the Street Parade, Schärer and his team spoke with people about techno, dancing and community. These personal statements provided the material for three audio collages and a video projection, which aimed to give visitors to TECHNO a feeling for how people are currently accessing techno culture and the spaces it inhabits.

From the basement, through the maze and onto the roof – and back again

What is now the Toni Campus was once Europe’s biggest milk-processing operation, occupying 83,000 square metres on the edge of the industrial district. The site was closed in 1999, with this whole space suddenly becoming available. Three clubs were set up there in the years that followed, with Schärer remembering the club Toni Molkerei as a minimalistic space where people came to dance, but with room for many other formats too. Art and design were combined with music, and sometimes more extravagant elements such as table tennis. Also in the basement, but at the other end of the building, was the Rohstofflager. “This was a large club, featuring a huge sound and lighting system in a hall painted black. It hosted raves with some of the best-known international DJs of the time.” Right at the top was the Dachkantine, probably the most legendary of the three Toni clubs, where the aesthetic, the programme and the crowd were more aligned with the subculture. “It was musically eclectic, with input from lots of collectives with connections to the squatting scene. The Dachkantine looked like something you might imagine from the Fusion Festival or a Berlin club in the ’90s: shabby chic with wood, carpets and sofas. A lot of things were reclaimed from the former staff canteen, but arranged very deliberately.” Early morning sunrises, as seen from the roof terrace, were a particular treat. The clubs were linked by endless corridors and halls, leading to artists’ studios, exhibition spaces or temporary sports facilities. “A real maze”, as Schärer describes it, where a wide range of ideas took shape. With the closure of the Rohstofflager in 2010, the last club left the former Toni dairy site, and work began to convert it into the university campus. The surrounding area changed fundamentally too, with industrial buildings making way for hotels and residential or office space. And the people who had made the west of Zurich a centre for subculture waved goodbye as well.

Reclaiming lost freedom

Has techno become something of a museum piece? Nicholas Schärer feels this question is misplaced, as the city is more than entitled to celebrate the history of its innovative club culture. But life is happening today. And then you have the question of how young people might once again enjoy easy access to spaces they can shape for their own ends. And, in doing so, reclaim a kind of freedom that was largely lost with the transformation of the west of Zurich and other districts. Whether it be for electronic music, unconventional events or something totally different that can only emerge this way.